- Home

- Tariq Shah

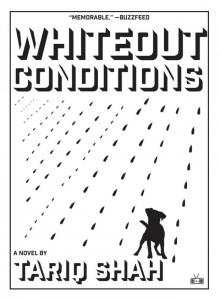

Whiteout Conditions

Whiteout Conditions Read online

Two Dollar Radio

Book too loud to ignore

WHO WE ARE TWO DOLLAR RADIO is a family-run outfit dedicated to reaffirming the cultural and artistic spirit of the publishing industry. We aim to do this by presenting bold works of literary merit, each book, individually and collectively, providing a sonic progression that we believe to be too loud to ignore.

TwoDollarRadio.com

@TwoDollarRadio

Proudly based in

Columbus

OHIO

@TwoDollarRadio

/TwoDollarRadio

Love the

PLANET?

So do we.

Printed on Rolland Enviro.

This paper contains 100% post-consumer fiber,

is manufactured using renewable energy - Biogas

and processed chlorine free.

Printed in Canada

All Rights Reserved

COPYRIGHT © 2020 BY TARIQ SHAH

ISBN 9781937512910

Library of Congress Control Number available upon request.

Also available as an Ebook.

E-ISBN 9781937512927

Book Club & Reader Guide of questions and topics for discussion is available at twodollarradio.com

RECOMMENDED LOCATIONS FOR READING WHITEOUT CONDITIONS: Upon a Greyhound bound for Rockford by midnight, within view of a bare forest, a hospital, or pretty much anywhere because books are portable and the perfect technology!

ANYTHING ELSE? Yes. Do not copy this book—with the exception of quotes used in critical essays and reviews—without the prior written permission from the copyright holder and publisher. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means.

WE MUST ALSO POINT OUT THAT THIS IS A WORK OF FICTION. Any resemblances to names, places, incidents, or persons, living or dead, are entirely coincidental or are used fictitiously.

… The dark adjusts

itself, settles its wings inside you. The shadows that

strut the dark

open and fold like hope, a paper fan, violence

in its pitch and fall, like waves—above them, the usual

seabirds, their presumable

indifference to chance, its

blond convergences… As when telling cruelty apart

from chivalry can come to seem irrelevant, or not anymore

the main point …

—Carl Phillips

you won’t get far by yourself.

it’s dark out there.

there’s a long way to go.

the dog knows.

—Robert Creeley

Table of Contents

Chapter I

Chapter II

I

With the last of my loved ones now long dead, I find funerals kind of fun. Difficult to pinpoint what it is. I’m drawn to them. Call it an article of faith. They aren’t what they used to be. And I am not my old self.

I’m thinking of the deep boom and hush after the pastor shuts his thick tome of hymns, and the heavy groans of the pews when everyone kneels.

What comes to mind are the high school boneheads loafing around the holy water stoup, too rad to grieve, or who never learned how, never learned that it is learned, like formal dinner etiquette, or gallantry in the face of certain peril.

It’s the secret stoner altar boy glad to swing his censer, the blown-apart family uniting for a minute to ridicule the reverend’s lopsided toupee. The great uncle with trouble reading in the filmy pulpit daylight, his index finger trembling.

Or when I drift off during an old man’s eulogy, only to get clocked in the forehead with a truth bolt changing my vision of retired Honda dealers forever. At a certain point the mileage accrued by hearts, like any muscle car, is just too fantastic.

Once it was the apoplectic rage of a niece pacing the narthex, denied the chance to damn her uncle to hell, tell him she loved him.

Sometimes it’s the waterworks, other times, the hearse.

It was the pious haste with which Muslim grievers dug the grave, buried the doctor, how that left everyone in a swarm, a bit head-spun, and forgetful the dead’s dead.

The wholehearted embraces given me by Evangelists to whom I didn’t speak at all, the fervent strangers touched I’m there, who cared I’d come, each hug verging on a submission hold, and it’s the bright secret that won’t quit tap-dancing behind my benign expression that I keep from them, that ensures their enthusiasm and sincerity are squandered on me.

Or a jogger, sometimes there will be a jogger, who will gawk like a rubbernecker, or just keep jogging, maybe go a little faster.

Seeing my buddies in suits for the first time, a grandmother past remembering why she’s there. Sometimes it’s as simple as a song of tribute sung by someone who can’t sing at all. You see people for who they are, and they don’t mind being seen, and it’s lovely in a way, that unabashed flawed-ness in the face of such heavy exposure, perhaps never to happen again.

All of which would likely be overlooked were I choked up by the stiff in the coffin.

It’s everyone wondering what I am doing there. It’s all the suspicious looks—why aren’t you sad like us? How they all ping off me.

Shadowing Death. Handling death like a snake charmer fishing cobras from his wicker basket, wholly impervious to fang and by now safely immune to its venom. And how sometimes, it’s the other way around.

Funerals are kind of fun, yes. I’ve cultivated a taste. It’s become a kind of social pursuit. It was a kink, of a kind.

But now Ray. I see his face, the one in the photograph the reporter in the field held up to the camera, with its fresh acne, and his right cheek’s dimple deeper than I remember, and him already taller than his mother, and I’m having trouble sustaining a positive mental attitude. Now, a python’s double-jointed jaws, Death opens wide. But, what do I know about such creatures?

*

I consider putting all of this to big old Hank, who, after sucking down his third screwdriver beside me on the plane, gets talkative, wonders why I’m flying, what with the weather—Chicago had a heavy white Christmas chased by a short thaw, but the Channel 9 weather guy predicts a monster on the horizon. I say, “funeral,” as though it were a destination wedding.

He’s a day trader on the futures market. Manicured nails, plump baby face, silver cufflinks. He would think I’m horsing around, some sort of wise guy, and eventually expect a rational explanation, request a change of seats. But I’m coming clean.

“Ever play with matches as a kid?” I ask.

He clears his throat and nods, uncertain, as a pocket of choppy weather jostles the cabin, making Hank spill half his drink all over his nifty polka dot tie. After glancing down the aisle, he sucks the alcohol directly from the raw blue silk.

I pretend not to notice. Outside the window, Illinois’ patchwork of snow-dusted farmland scrolls underneath us, the color of month-old bread. The freeways and interstates carving colossal esoteric runes into it. The tiny black trees that suture it all together.

“Vince and I,” I say, “we used to slick our arms in Aqua Net and light ourselves on fire. Our new rippling blue sleeves blowing our minds. Funerals are like that now. Only everyone else is burning for real, and I’m completely fine.” I down the dregs of my coffee. “You ever do that?”

Hank buckles his safety belt, says he can’t stand landings, so I drop it. All this turbulence is getting to me, too.

*

I’m back home, braving O’Hare’s crowds—the holidays are through but concourse K is still a nightmarish glut of holly jolly backwash—slowpoke vacationers and duty-free shopahol

ics, Bing Crosby, and on-sale candy cane pyramid displays that all hound me faster for the exits.

It’s been a few years since I last saw Vince, who is on his way to get me out of here. We are off to Big Bend, to bury what’s left of his little cousin—Ray.

I heard about it on the morning news. I caught the tail end of the broadcast. The young face on the screen seemed an organic extension of something startling in its familiarity to me. The sensational nature of the incident pushed the story into wider media markets, I think. All the way to the East Coast.

So I gave Vince a call. I said I would come out. Give a show of support. Though I could have done less, I said it was the least I could do. Vince and his family sort of took me in after my own family’s disintegration.

The last time I saw Ray, I think, he was eight and I had just finished school. It was Vince’s birthday, middle autumn sometime. We cooked out. I remember Vince giving Ray his first taste of liquor, a swig from his Solo cup of Captain Morgan-and-whatever. Then spending the afternoon with them, shooting hoops in the drive, a few old folks in lawn chairs giving color commentary.

I remember watching Ray take that sip and Vince asking him, “How you like the taste of that?”

Ray made this sour face and said, “Beer’s better.” All the old folks ate that right up.

*

Slinking out past the baggage carousels, I have a post-flight cigarette that hits me so hard I swoon and gag like a rookie. But the parking garage fumes are a pleasant surprise. There is something I find nostalgic in the odor—all maple syrup and gasoline and the exhaust of a couple hundred idling taxicabs.

It’s been around five years since I’ve been back, and yet the puddles of slush by the wall where smokers shelter from the cruel gusts seem pitiless as ever, black and bottomless, an inky soup. I’ve missed even them.

Here the sky yawns white all day, then rips your head off like afterburners once the sun falls off the horizon. But when the cold comes, it comes like a dream, lugging the dark in a big black sack. And my body readjusts to the old song it knows by heart.

Planes arrive and depart. I know Vince’s circling around here somewhere, eyes peeled for someone I barely resemble now. I forget the kind of car he drives. It’s one of those big dependable American makes, four doors and the type of interior that’s not the leather option. The sort of car they don’t really make anymore, built with a once-fine quality and craftsmanship that has long since fallen out of practice. One of those made-up names that seems real.

But who knows what state it’s in. I smear out the smoke and wait on the outer traffic island for some kind of sign of him.

*

My dad never drank. That lent him a certain polish that Ruby, the other woman, must have found magnetic. He was always the designated driver, the voice of reason drumming sense into whomever was first to get rowdy at dinner parties, the one who really had no patience for Mom’s drunk juggling, and who more than anything, seemed to love to be the one to carry her up to bed.

I, on the other hand, loved it when she drunk-juggled. She always started off small. We’d be in the kitchen getting dinner ready, Dad either home or on his way.

“Hey, Ant, check this out,” she’d say—never when I was looking at her—and when I did, she’d have a couple fingerling potatoes going with one hand, while the other swirled a cast iron pan of chopped onions.

I would applaud her, then resume whatever homework, finger painting, or action figure brawl I’d been absorbed with.

A little bit later I would hear, “Uh oh!”

I’d look up again, and there’d be red and green bell peppers vaulting into the air. And then the salt shaker, a few tablespoons. By her third glass of merlot she’d be on to the chef’s knife, the cleaver, three or four champagne flutes.

One time, instead of the performance, I watched her face. Despite all that deadly hardware being airborne, her expression wasn’t one of deep focus, but simple amusement. She was only interested in my wonder, beholding this marvelous act, this peculiar talent of hers.

When she caught me looking at her, she winked. Then, calmly, she closed her eyes. Mom kept the spectacle going until a flute hit the floor, exploded, and we both laughed our heads off.

She was gifted with the hands of a surgeon. They never trembled, or fumbled, or missed, even in the numbing winter mornings and dark. Her hands were steady, clever instruments, and worked with an agile precision that I found beautiful to watch.

For a long time I believed her touch cured the migraines I would get as a boy. Her palms were dry and cool, soft as calfskin, and seemed to draw the pulse from its place behind my eyes. But the relief came from some other place, I think now.

She kept her nails plain, and whenever the Avon lady encouraged her to paint them, or worse, hinder them with Lee Press Ons, Mom would get this crooked kind of look and see her to the door.

She claimed she could do chainsaws, had juggled them before, but we only ever had the one.

After the divorce, her weird charm grew brittle. Over time, she became the sober, pragmatic one. What home had become eventually became normal, until high school started. Everything changes for everybody, but for us especially, since the doctors felt a lump in her left breast. Then a mass at the base of her spine. This was right around homecoming, and Dad, who had at least kind of still been around, began to venture further out to the periphery of our lives until he was more absent than present, more answering machine than man.

But she still drunk-juggled from time to time, around the holidays, or the date of their anniversary. I still clapped like hell. She died that fall, just before Thanksgiving. The funeral was sober, pragmatic.

I have no idea whether Ruby drinks, or whether it was his sobriety she found attractive, or just the veneer it cast—either way, he must have preferred her figure to Mom’s wildness. And I don’t hope he is dead but I act according to that assumption. When I find myself low on that, I simply wish it.

The way it goes. I don’t pull sour faces anymore—I figure dead or alive, he’s gone for good. That’s pretty reliable. It does the trick. Still—beer is better.

*

Vince lays on the horn when he sees me. I heave my bag into the trunk and hop in like we’ve done this a hundred times.

“Your hair is long,” I tell him. It’s past his collar, though it’s also receding.

“Need to get a cut soon. Caroline likes it.”

“So the lady next to me at the airport bar got bombed and would not stop pushing her dopey son’s deep funk band on me. Deep funk or free funk, I can’t remember. He goes to JUCO. He’s the next Ornette Coleman, so that’s something. No, it was liquid funk, but what that is I do not know. Playing a lunchtime set at the Cubby Bear tonight or tomorrow. Gonna be ‘a real toe-tapper,’ apparently.”

Vince doesn’t even smile. “Things are good with you, then.”

I shrug—at him, and at everything I could tell him, at all I could say in response, my hoard of thoughts and tidings and urges that want a voice, a breath. I keep them stashed. “Feels nice, riding in this behemoth again. How’s things with you?”

He twists around to scope out a gap in the traffic to merge into. “We’re managing,” he says.

The windshield has a hairline fracture knifing slowly toward the center of the pane, the one-knob-missing radio doesn’t seem to get anything but AM, and I’m up to my ankles in wadded Taco Bell trash, which I bury my feet in, searching for the floor.

“Could you not stomp all over my stuff, please? I need all that for work and if I give back a bunch of broke equipment to my boss…”

I hold up a plug head. “What, this?”

“That cable’s for the reciprocating saw. It’s not mine. Don’t monkey with it.”

“Maybe you shouldn’t leave it tangled up on the floor under blankets of garbage.”

“It was fine how I had it before you started getting your muddy, salty shoes all over everything.”

“Here, I’ll c

oil it up.” I root through the fountain cups and wrappers to the orange cord beneath it all and begin looping it.

“Eh, don’t worry about it,” he says. “They had a piano guy playing at the mall this year. Some Christmas thing. Thought of you for a second.”

“Flattered.”

Vince smirks. “Beneath you, forgot.”

“How are you, other than managing? What’s Caroline up to these days?”

“She and the kids are in Disney World right now. That was their Christmas gift—an arm and a leg of their old man’s. They’re staying outside the park though, at some high school friend of Caroline’s with a place in Kissimmee. Flying back sometime Sunday.”

“They must be a handful.”

“She made me zap my balls last month. Two’s just shy of too much for us.”

“Wendy was big on starting a family. Saw herself having five, six. A great big litter. Red flag right there, if there ever was one.”

Vince nods. “Who’s Wendy now?”

I wave away the question. “Ah, just a girl. You know. Came and went.”

Vince cuts in front of a van, into hectic traffic, his car spewing bluish exhaust behind us like a sad magician’s trick.

I just shrug.

The route gains familiarity, despite my time away. A few ancient billboards still stand, though they are largely dilapidated beyond recognition—just a smoky eye, half a restaurant logo ripping in the wind, the unnerving command Hurry!—being all that’s left of them. I struggle to find something to fill the vacuum of silence between us.

“Know any good songs?”

He shakes his head, and we’re quiet again.

As the road meanders west, forest thins into strip mall, and thick, crooked black cracks start riddling the road home.

“You missed our turn,” I tell him.

“No, I didn’t.”

Whiteout Conditions

Whiteout Conditions